Many skeptics question whether we can truly rely on the words of the disciples as recorded in the Gospels, simply because these accounts were written by Christians. The assumption is that once someone becomes convinced of a claim, their testimony is instantly biased and, therefore, unreliable. Having spent years as a detective, deeply involved in the scrutiny of eyewitness accounts, this concern is not foreign. In fact, some doubters will even go as far as to insist that any credible information about Jesus must come from a non-Christian source. But does this demand stand up to reasonable scrutiny, especially in the world of cold-case detective work?

As detectives, trust is not freely given to any eyewitness—regardless of their background or worldview. Experience in law enforcement, especially in high-stakes realities like courtroom testimony, has a way of making one rightfully cautious. The goal is never simply to accept what a witness claims. Rather, every statement must be tested. Not only the words, but also the character, sequence of events, changes in story, potential bias, and connections to the event are examined. This process follows a strict and methodical approach, and the same must be applied to ancient eyewitness accounts like those in the Gospels.

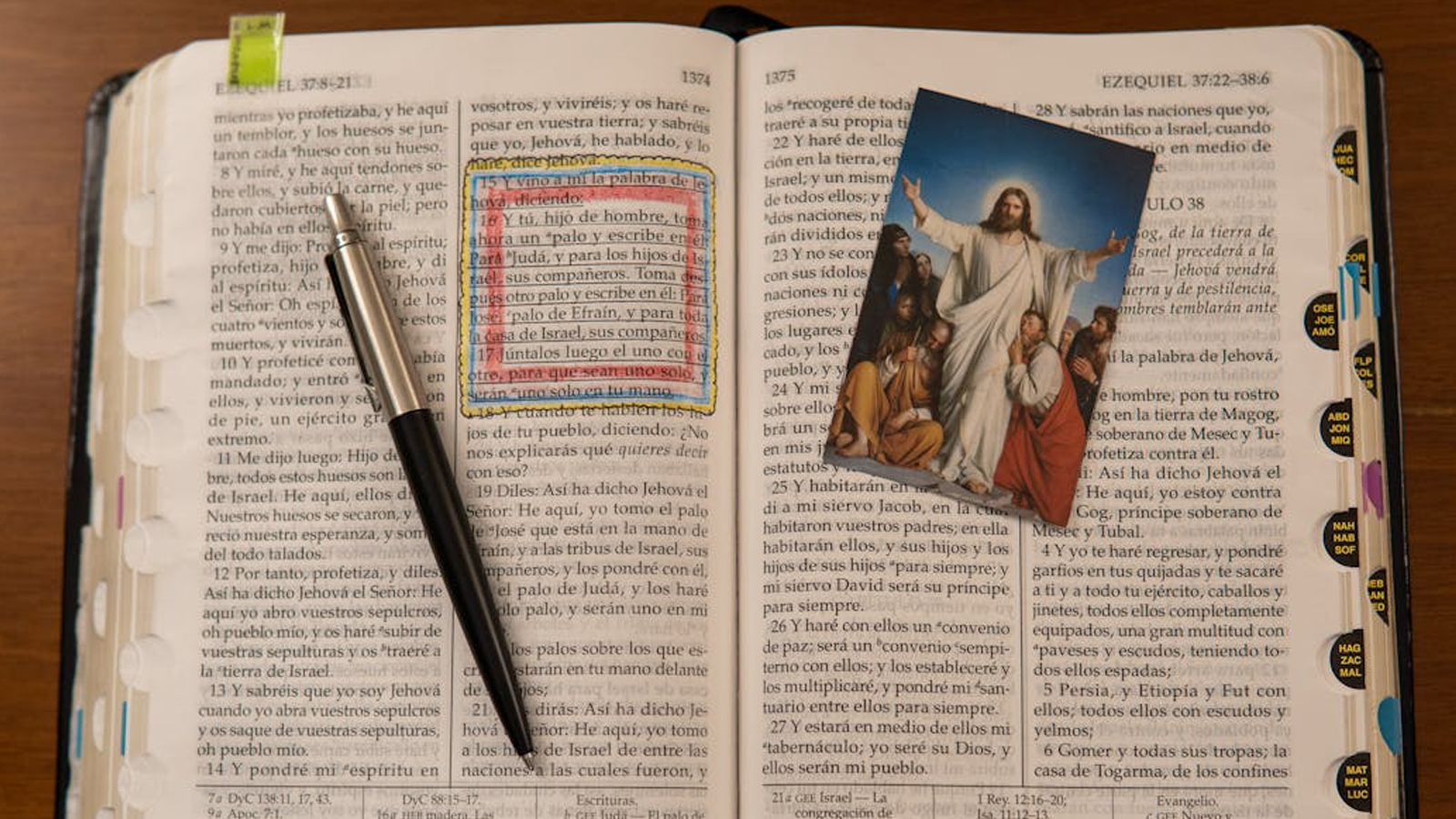

There are four critical questions that must drive our examination of any eyewitness, ancient or modern: Were they actually present to see what they claim? Can their account be corroborated in some fashion, even indirectly? Have the key elements of their story shifted over time? And finally, do they possess ulterior motives or bias that would tempt them to lie or embellish? This is not a uniquely religious or anti-religious method; it is simply good investigative practice. The court system depends on separating trustworthy eyewitnesses from unreliable ones.

When this same grid is applied to the authors of the Gospels, something remarkably consistent emerges. One common objection is that since the Gospel writers eventually became Christians, their claims are tainted and thus unreliable. But this objection misses a crucial point about the very nature of the disciples’ journey. The core issue is not who they became at the end of their journey, but who they were at the start, and whether the transformation was rooted in true experience.

Take Matthew, for example. When encountered in the Gospel narrative, Matthew is not presented as an eager disciple or someone with vested religious interests. He is a tax collector—an outsider, a man viewed by his contemporaries with suspicion rather than reverence. He was not a devotee of John the Baptist, nor was he a friend of Peter, Andrew, or the others. In fact, Matthew, known also as Levi, is portrayed as a man who is far from expectations of a coming Jewish Messiah. His day-to-day life is consumed with the unglamorous business of tax collection, likely making him an outcast in his own community.

Yet, when Jesus encounters him, calls him by name, and invites him into a new way of living, Matthew agrees to step away from everything he knows. Over the course of the next several years, he witnesses firsthand a series of unprecedented events—the teachings, miracles, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Only through the totality of these experiences does Matthew become a committed follower, and it is this journey from skeptic to believer that gives his witness its particular strength. To insist that Matthew’s account must be disregarded because he ultimately became a Christian is to misunderstand how belief is formed through experience. If you saw what he saw, you might also find yourself forever changed.

Furthermore, if one is truly looking for a non-Christian source to recount the events of Jesus’s life, then Matthew initially fits the bill more closely than we realize. At the outset, he has nothing to gain and everything to lose by aligning himself with Jesus. His transformation is itself part of the evidence. What bias could have propelled him at the beginning, when there was no widespread Christian movement, only risk and potential alienation? If one is truly looking for a non-Christian source to recount the events of Jesus’s life, then Matthew initially fits the bill more closely than we realize. Share on X

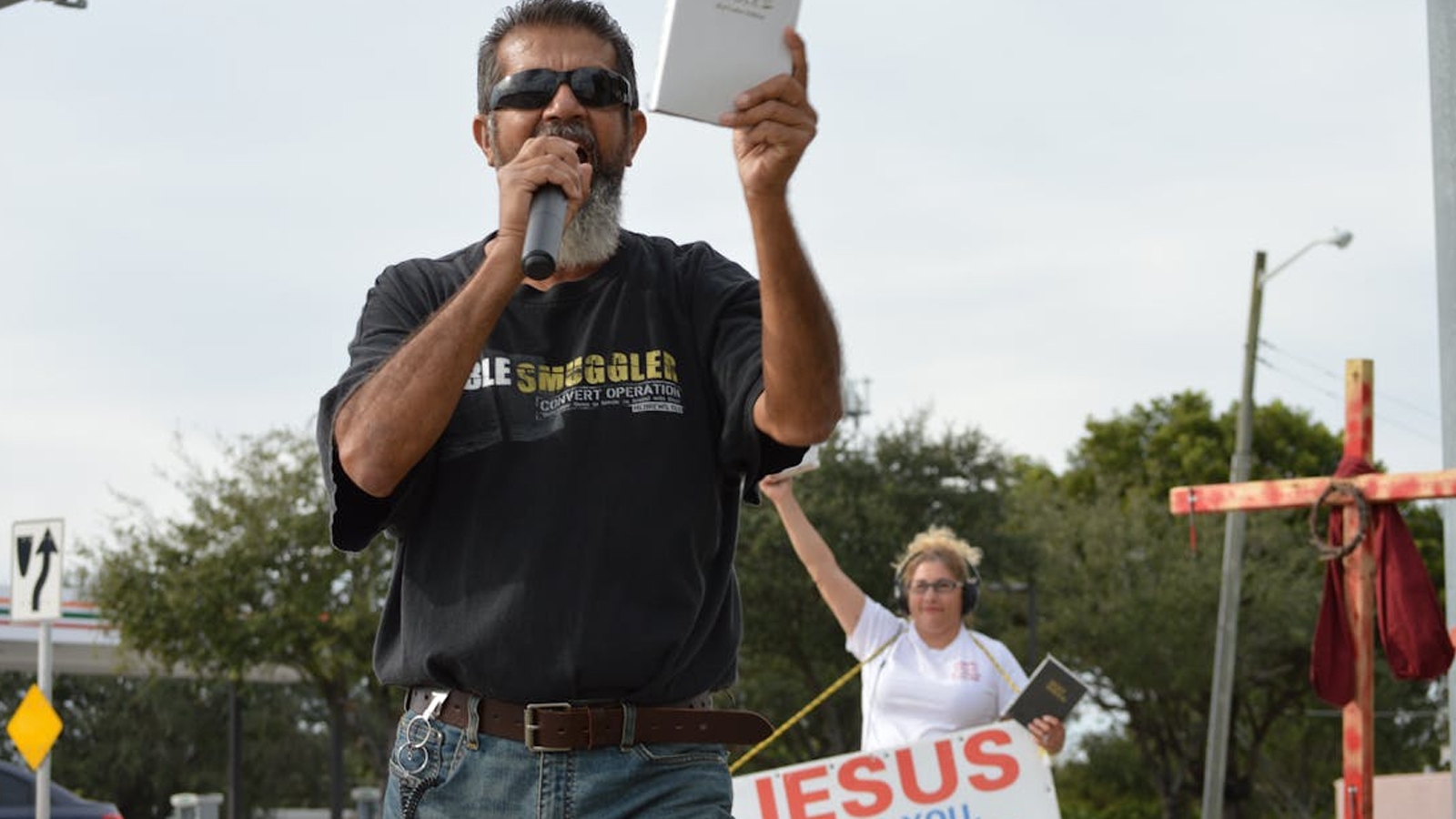

The call for an outsider’s perspective is, at its core, a desire for objectivity. But objectivity doesn’t mean lack of conviction; rather, it means that one’s convictions are the result of honestly encountering something true. In both modern and ancient contexts, the best eyewitness testimony often comes from those who were closest to the action—those changed by what they saw, not those who passively observed from a distance.

So, are the disciples’ words in the Gospels reliable? Only if they pass the same rigorous examination as any other eyewitness. And when that test is applied, what we find is not a group of men manufacturing stories out of blind devotion, but rather a set of individuals who, compelled by what they experienced, authored accounts that withstood the scrutiny not just of their own generation, but of centuries of serious investigation. Their initial skepticism, subsequent conviction, and willingness to endure hardship for their claims are not marks against their credibility, but confirmations of it.

In the end, the right response is not to dismiss the testimony of those who became Christians after experiencing Jesus, but to investigate whether their transformation has its source in real, historical events. Just as in detective work, it is not the presence of belief that invalidates a witness; it is whether belief was earned by experience and evidence, and whether their account holds up when put to the test. In that light, the disciples’ words continue to ring with credibility for those willing to evaluate them honestly.

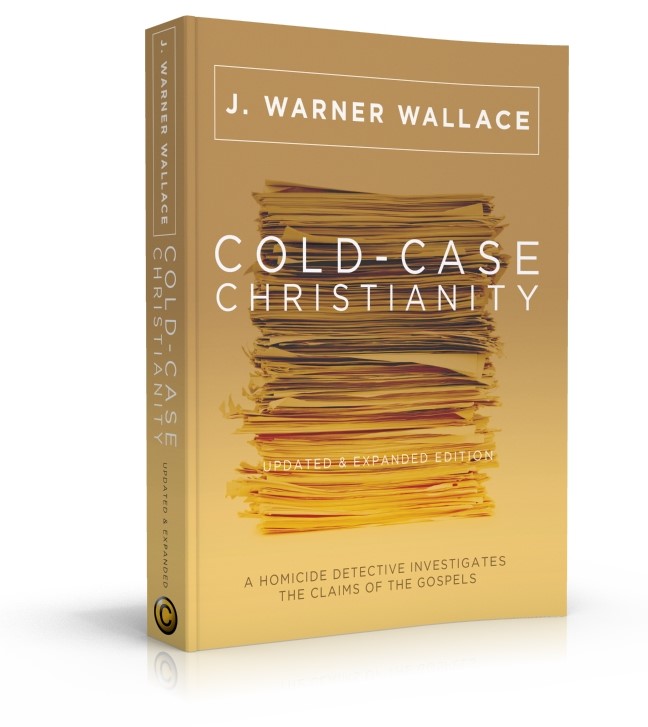

For more information about the reliability of the New Testament gospels and the case for Christianity, please read Cold-Case Christianity: A Homicide Detective Investigates the Claims of the Gospels. This book teaches readers ten principles of cold-case investigations and applies these strategies to investigate the claims of the gospel authors. The book is accompanied by an eight-session Cold-Case Christianity DVD Set (and Participant’s Guide) to help individuals or small groups examine the evidence and make the case.

For more information about the reliability of the New Testament gospels and the case for Christianity, please read Cold-Case Christianity: A Homicide Detective Investigates the Claims of the Gospels. This book teaches readers ten principles of cold-case investigations and applies these strategies to investigate the claims of the gospel authors. The book is accompanied by an eight-session Cold-Case Christianity DVD Set (and Participant’s Guide) to help individuals or small groups examine the evidence and make the case.