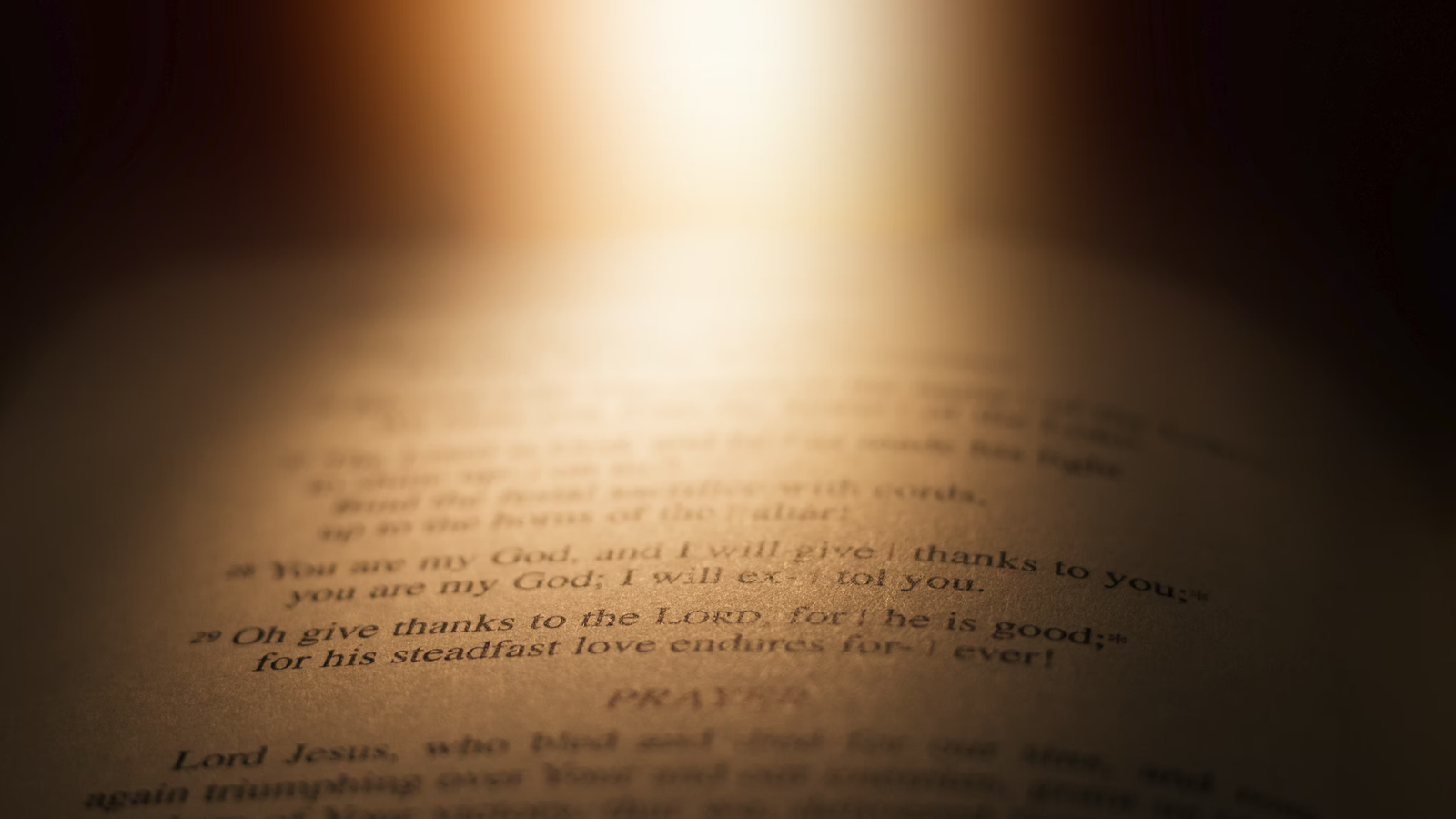

Central to the claims of the New Testament is the assertion that Jesus was crucified and subsequently rose from the dead.[1] In his Gospel, written circa 80-85 AD,[2] Luke depicts Jesus’ appearance to his disciples after his death and burial, “[Jesus said,] ‘See My hands and My feet, that it is I Myself; touch Me and see, because a spirit does not have flesh and bones as you plainly see that I have.’ And when He had said this, He showed them His hands and His feet.”[3] It is critical to Christianity that Jesus not only lived as a historical person, but actually rose from the dead. In an effort to support the Biblical claim of resurrection, Christians have adopted a number of approaches for supporting the historical claim of resurrection. However, some skeptical scholars reject the use of history to draw such a conclusion. Central to the claims of the New Testament is the assertion that Jesus was crucified and subsequently rose from the dead. Share on X

Bart Ehrman, a leading New Testament scholar, has previously defined the mission of history as follows: “Historians try to establish to the best of their ability what probably happened in the past.”[4] But when approaching the question of Jesus, Ehrman rules out the resurrection categorically, saying, “A “miracle” can never be shown, on historical grounds, to have happened,” in part, “Because doing so requires a set of presuppositions that are not generally shared by historians doing their work.”[5] Using this framework, one can never conclude that Jesus’ resurrection was a historical fact (causing quite a problem for the truth of Christianity as a whole).

But is Ehrman correct that the problem is a lack of shared presuppositions on the part of historians? This is a curious claim; the belief that miracles cannot occur is not a default position. Instead, Ehrman seems to be admitting that the problem for historians is that they hold a presupposition (that miracles cannot act as a historical conclusion). Historians then do not have a too-few shared presuppositions, but rather too many.

Ehrman does attempt to support the exclusion of miracles by historians due to their rarity, explaining, “Miracles are not impossible. I won’t say they’re impossible… I’m just going to say that miracles are so highly improbable that they’re the least possible occurrence in any given instance.”[6] Ehrman is not wrong with regards to miracles’ rarity; by definition miracles are exceptions, not rules. However, it does not necessarily follow that a miracle is de facto the “least possible occurrence” for every conceivable scenario. When investigating any claim that a miracle has occurred it is wise to keep in mind the rarity of such events, but one does not need to completely write them off from the outset.

To see the weakness in Ehrman’s approach, let us consider the argument for the resurrection made by Christian apologists Gary Habermas and Michael Licona as it compares to a popular alternative theory. Habermas and Licona offer five pieces of data which are “strongly evidenced… [and] granted by virtually all scholars on the subject, even the skeptical ones,” these being 1) Jesus died by crucifixion, 2) Jesus’ disciples believed that he rose from the dead and appeared to them, 3) the Church persecutor Paul was suddenly changed, 4)the skeptic James, brother of Jesus, was suddenly changed, and 5) the tomb was empty.[7] The Christian explanation for these facts is that Jesus really rose from the dead and appeared to the disciples and others, causing radical transformations.

A popular alternative theory is the “hallucination theory” which suggests that after Jesus’ death his followers only believed they had seen the risen Jesus when, in reality, he had not been raised. However, the hallucination theory struggles on several grounds, including the fact it does not explain the empty tomb, the kind of group hallucinations required by the theory are virtually unknown to science, and the fact it requires multiple groups of people to have highly improbable hallucinatory or otherwise imagined experiences of the risen Jesus at different times and in different places over the course of 40 days.[8] However, in order to remain consistent with Ehrman’s approach, if one had to choose between the options of the resurrection or hallucination theory, one would have to accept the hallucination theory and its many weaknesses (weaknesses not shared by the claim Jesus resurrected from the dead). No matter how improbable any theory could be, Ehrman’s schema has decided from the outset that it is preferable to accepting the resurrection.

If the goal of history is, as Ehrman claims, “to establish to the best of [our] ability what probably happened in the past,” then one cannot discount miracles from occurring before the question is even asked. Given the known historical facts surrounding Jesus and the early Christian movement, it is more reasonable to conclude that the resurrection of Jesus actually occurred in history than to accept an opposing theory such as the hallucination hypothesis.

[1] In 1 Corinthians 15 the Apostle Paul states the entirety of the Christian faith stands or falls on this singular claim.

[2] Gary Habermas, “Q&A Topics,” GaryHabermas.com, accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.garyhabermas.com/qa/qa_index.htm. See also, Bart Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 109.

[3] Luke 24:39-40.

[4] William Lane Craig and Bart Ehrman, “William Lane Craig and Bart D. Ehrman Debate the Question ‘Is There Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus?’” Southern Methodist University, accessed November 14, 2021. http://www. physics.smu.edu/~pseudo/ScienceReligion/Ehrman-v-Craig.html.

[5] Bart Ehrman, “Historians and the Problem of the Miracle,” The Bart Ehrman Blog, last modified November 15, 2013. https://ehrmanblog.org/historians-problem-miracle-members/.

[6] Ehrman, “William Lane Craig and Bart D. Ehrman Debate the Question ‘Is There Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus?’”

[7] Gary Habermas and Michael Licona, The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus (Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, Inc, 2004), 47-77. It should be noted, Habermas clarifies that the fifth point is accepted by “ roughly 75 percent” rather than “virtually all” scholars.

[8] Gary Habermas, “Explaining Away Jesus’ Resurrection: The Recent Revival of Hallucination Theories,” Christian Research Journal, vol. 23, no. 4, https://www.garyhabermas.com/articles/crj_explainingaway/crj_ explainingaway.htm.

Jimmy Wallace is a detective who holds a BA in Psychology (from UCLA) and an MA in Theology - Applied Apologetics (from Colorado Christian University).

Lester C Verigan Jr

January 7, 2022 at 10:22 am

My only question is that if Luke wrote his account ca. 80-85 AD, why didn’t he include the destruction of the city of Jerusalem and the temple? This was prophesied by Jesus, and would have been one of the most significant pieces of evidence that He was/is the Messiah. On the other hand, Luke’s full account, comprised of his Gospel and the book of Acts, closes prior to Paul’s martyrdom, which took place around 68 AD. If the second part of Luke’s account (the book of Acts) ends prior to 67 AD, then obviously the first part (the Gospel of Luke) would have had to be written even earlier than that.

Justin

January 7, 2022 at 6:26 pm

I applaud in how you affirm the importance of presuppositions. Skeptics should at least come to the NT with an open mind that miracles are probable.

Michael Leonard

March 21, 2022 at 11:21 am

When it comes down to probability of resurrection it’s clearly either a legion or actually occurred that are really the only two possibilities. Modern medicine really rules out swoon theory( surviving crucifixion) or mass halilucation happening at multiple times. Historical evidence for resurrection was much more plentiful than I first imagined.