Don’t trust popular opinion: “We work the cases nobody wants to work, the ones where it’s like, ‘Hey, we’re not sure this case is winnable.’ For the most part everyone has abandoned it for years. We’ve had cases where the victim’s family was absolutely unconcerned and in fact didn’t even want us to work the case. Why would you want to file a case when nobody’s pressuring you? Nobody even knows about this case, so all you can do is bring shame to our agency. To file a cold case results in one of two things: a win, which is fine, or a loss, which makes you look really bad.”

Find jurors who can connect the dots: “People don’t realize that these trials are won and lost in jury selection. That’s typically an aspect that no one gets to see, because typically no reporters are there. But that’s where the most masterful work is done. For our cases, you have to ask the right kind of questions that along the way end up teaching the jury about circumstantial evidence—because they’re not going to know. I don’t want it to sound like we’re trying to brainwash juries. We’re trying to educate them in a way that we think is helpful to the kind of case we think we’re going to present. Both sides do this.”

Never consider any detail too small: “No one’s going to know the case as well as we do. We simply spend more hours on it. That’s what happened on the Douglas Gordon Bradford case. We knew the case far better, and I think we even knew their witnesses better, than the defense knew their witnesses. We actually call them. I’m the kind of person that does not want the defense to find a witness I haven’t first talked to, so if there are 50 potential witnesses, I’m going to have to talk to all 50.”

But look at the big picture: “My background is in the visual arts, so I’m always looking at crime scenes, trying to assess their composition the same way you would assess the composition of a piece of art. I’m inclined to look at it and ask myself why is every piece in the position that I see it in. I will very rarely bring a case to the D.A. that’s not visually represented in some way. So if you’re going to say, ‘Why should this piece of evidence be considered important?’ Let me show you why: If the victim had left it here, it would look like this; if it was part of the original scene, it would look like this—but this is how it really looks. You can learn a lot from blood spatter. If a knife blade is pointing outward, it’s going to make a certain kind of spatter. Blood spatter can actually tell you where the attack occurred. It can tell you at times about how tall the attacker was, or whether the guy was lying down. I love that stuff because visually you can communicate that to a jury.”

And never take human nature for granted: “John and I don’t work serial killers. Serial killers are the ones that you go next door to their neighbor after it’s over and you say, ‘I just arrested your neighbor for a murder,’ and he goes, ‘Man, I thought that guy was a nut job. It smelled bad over there. The lights were always on.’ All this weird behavior. But when you arrest a cold case killer and knock on their neighbor’s door, they’re going to say, ‘No way! That guy’s got keys to my house. He watched my kids when I’m not home.’ The difference is serial killers are constantly in the midst of their killer instincts…. People like Doug Bradford—or any of the other cold case murders we’ve worked over the years—demonstrate for us something even worse and in some ways more insidious: an ability that all of us have to do exactly what they did. The only difference is that, but for the grace of God, nobody has pushed us to that point. But if somebody did, we would be no different from Bradford. That guy is in all of us.

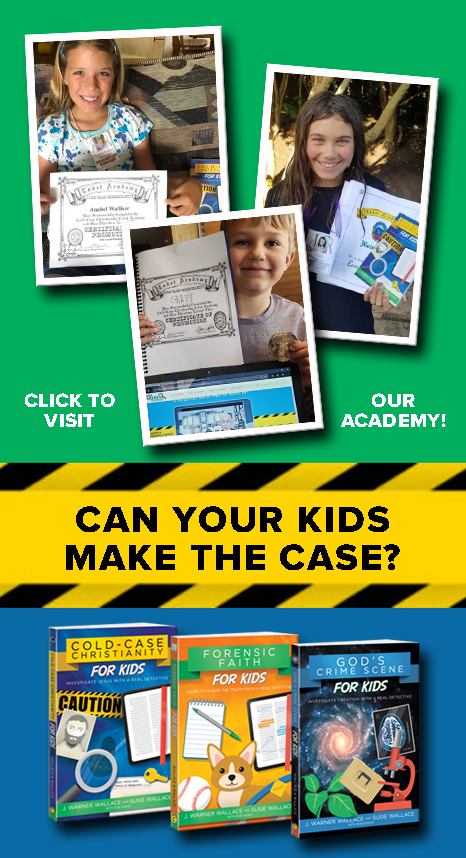

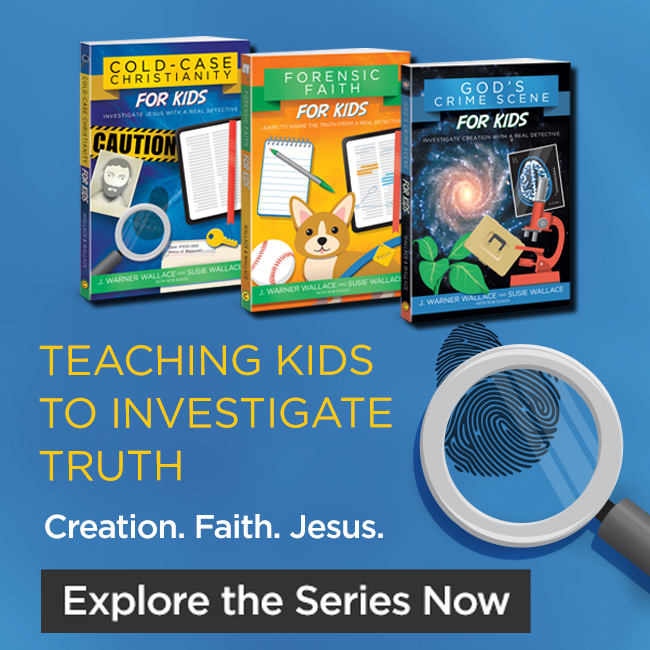

These are but a few of the principles we’ve employed time and time again as we’ve investigated and prosecuted cases over the years. Christianity is relatively unique among theistic worldviews in that it is grounded in a specific claim related to an event in the distant past: the Resurrection. Cold-cases are also grounded in a claim about an event in the distant past; many of the techniques and approaches we take in investigating these murders can be applied to the Christian worldview. For more on this approach, I hope you’ll read, Cold-Case Christianity: A Homicide Detective Investigates the Claims of the Gospels and God’s Crime Scene: A Cold-Case Detective Examines the Evidence For A Divinely Created Universe. On an aside, many thanks to the California Peace Officers Association for awarding our investigation of the Lynne Knight Case as the “Best Cold-Case Solved” this year.

J. Warner Wallace is a Dateline featured Cold-Case Detective, Senior Fellow at the Colson Center for Christian Worldview, Adj. Professor of Christian Apologetics at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, author of Cold-Case Christianity, God’s Crime Scene, and Forensic Faith, and creator of the Case Makers Academy for kids.

Subscribe to J. Warner’s Daily Email

J. Warner Wallace is a Dateline featured cold-case homicide detective, popular national speaker and best-selling author. He continues to consult on cold-case investigations while serving as a Senior Fellow at the Colson Center for Christian Worldview. He is also an Adj. Professor of Christian Apologetics at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, and a faculty member at Summit Ministries. He holds a BA in Design (from CSULB), an MA in Architecture (from UCLA), and an MA in Theological Studies (from Gateway Seminary).