The word “contentment” traces its roots back to the early to mid-fifteenth century, originating from the Latin term contentus, the past participle of continere, meaning “to contain” or “to hold together.” This origin is fitting, for discontentment often begins when we step outside the “container” of our own lives, looking outward with longing or envy. Jackson’s story illustrates this well: his dissatisfaction grew the moment he started comparing himself to Stephen, peering beyond his own “enclosed” existence and into someone else’s.

Today, contentment is commonly defined as being “satisfied with your life or the situation you are in.” But contentment is not some distant prize to be won later; it is a choice made within, independent of external circumstances. Charles Spurgeon wisely noted, “It is not how much we have, but how much we enjoy, that makes happiness.” Contentment, then, is an inside-out decision—a decision worth making, especially when weighed against its alternative.

Psychologists and sociologists alike have linked contentment closely with human flourishing. Studies show that content people report higher well-being and describe contentment as a kind of “unconditional wholeness,” a state that persists regardless of what life throws at us. This sense of satisfaction is not merely a luxury but a necessity for thriving. It shields us from destructive impulses, such as envy, which can poison our minds and relationships.

The Bible addresses envy head-on, calling it “covetousness” and listing it among the Ten Commandments’ prohibitions. The word envy itself comes from the Latin invidus, meaning “envious” or filled with “hatred or ill-will,” and invidere, “to hate,” “look at with malice,” or “cast an evil eye.” The phrase “giving someone the evil eye” captures this perfectly—envy is a malicious glance that wishes harm on another because of what they possess. It is a corrosive force, one that has long been recognized as destructive.

Some modern researchers try to soften envy’s blow by distinguishing “benign envy” from “malicious envy,” but make no mistake: envy’s corrosive impact remains profound. It arises when we compare ourselves unfavorably to others, and research confirms these comparisons damage our well-being. Those who envy tend to suffer poorer mental and physical health. Envy breeds depression, feelings of inferiority, anger, and resentment. It even diminishes gratitude for one’s own blessings and traits. True satisfaction is found not in comparison or coveting, but in the quiet confidence of a life well-lived Share on X

Envy doesn’t just hurt us internally; it warps our relationships. Envious individuals are more likely to deceive friends and speak ill of them behind their backs. Envy has even been linked to violent acts, including murder. Young people, in particular, are vulnerable to envy’s destructive power—perhaps because social media acts as a constant “petri dish” for unfavorable comparisons. Platforms that showcase carefully curated highlights of others’ lives foster “malicious envy,” leading to increased depression and dissatisfaction. Users often feel inadequate, jealous, and unattractive as they measure themselves against idealized images. This downward spiral harms their “affective well-being,” the emotional quality of their lives.

Another vital ingredient in human flourishing, closely tied to contentment, is purposeful work. Thomas Edison famously said, “Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work.” Meaningful employment is more than a paycheck; it is a cornerstone of well-being. Research shows that purposeful work improves both physical and mental health, reducing depression and anxiety while boosting resilience. The benefits extend beyond the workplace or the hours spent on the job. Purposeful work enhances happiness, life satisfaction, confidence in one’s identity, and connection with loved ones.

Work matters not just as a deterrent from wrongdoing but as a vital contributor to flourishing. When we engage in work that aligns with our values and purpose, we find ourselves more content and more whole. We are less likely to look outside ourselves with envy because we are anchored in the satisfaction of meaningful effort.

In the end, contentment is a choice—a decision to find peace within, to resist the corrosive pull of envy, and to embrace purposeful work. It is a state of being “contained” and “held together” from the inside out, regardless of external circumstances. True satisfaction is found not in comparison or coveting, but in the quiet confidence of a life well-lived.

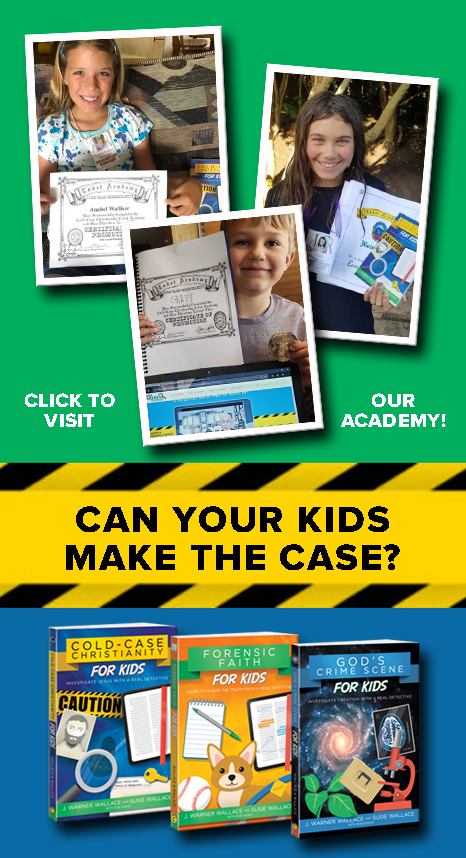

To learn much more about the importance of contented work and how this traditional value contributes to human flourishing and establishes the reliability of the Biblical record, please read The Truth in True Crime: What Investigating Death Teaches Us About the Meaning of Life.