Everyone, at some point, faces hopelessness. Sometimes it creeps in over a personal struggle—a relationship that seems beyond repair, a job that feels like a dead end, or a diagnosis that shatters the illusion of control. Other times, it rises from the world around us: headlines about war, injustice, or a planet in peril. If you’ve ever caught yourself thinking, “That’ll never change,” “Good luck with that,” or “No one can help me,” you’ve brushed up against hopelessness. It’s the sense that nothing will get better, that the story won’t end well.

Hopelessness and depression are close companions. In fact, you’d be hard-pressed to find a clinical description of depression that doesn’t mention hopelessness in some form. The statistics are sobering. Globally, around 300 million people live with depression or persistent hopelessness. In the United States alone, more than 18 million adults experience depression each year—roughly one in ten. It’s now the leading cause of disability in the country.

And it isn’t just adults. Children and teenagers are not immune. In a nationwide study of kids ages 3 to 17, more than 2.7 million had experienced depression. Among teens, hopelessness is rising fast. One study found that nearly 30% of boys and a staggering 60% of girls reported “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness.” This isn’t just a phase—it’s a crisis.

Hopelessness often shows itself in subtle ways. Maybe you stop watching the news, convinced nothing will change. Maybe you lose interest in hobbies or friendships that once mattered. Maybe you find yourself settling into a rhythm of despair, convinced that this is just the way things are. Why does this happen? Some researchers point to social media as a major culprit. The longer we scroll, even passively, the more our mood sours. The endless stream of bad news, outrage, and comparison leaves us convinced the world is broken beyond repair. One study found that nearly 70% of people are no longer optimistic that anything will improve.

This kind of despair is more than just unpleasant—it’s dangerous. Hopelessness increases feelings of loneliness and isolation. It makes it harder to bounce back from setbacks or trauma. People who feel hopeless are more likely to seek out antidepressants or therapy. But the most chilling statistic is this: hopelessness is strongly linked to suicide. It’s not just a feeling; it’s a risk factor.

The toll isn’t just mental. Hopelessness takes a physical form, too. People who feel hopeless often report fatigue, dizziness, and a lack of energy. Studies repeatedly link hopelessness to cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. Hopelessness is also associated with higher levels of pain, cancer, and chronic illness. It even predicts how well we recover from illness. Cancer patients with little hope have a lower quality of life and a higher awareness of symptoms. In fact, hope can predict survival rates in advanced cancer, intensive care, post-surgery, and even organ transplants. Diabetics with hope are more likely to stick to healthy habits. The bottom line? Hopeless people live shorter, less healthy lives.

Philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer put it plainly: “People cannot live without hope; this is one of the statements I can defend without any reservations.” Hope is the engine that keeps us moving. It drives us to act, to persevere, to flourish. Hopeful people are better at communicating their feelings, building relationships, and thriving at work. They make better parents, and their children are less likely to take dangerous risks. Helen Keller, who knew more than her share of adversity, wrote, “Optimism is the faith that leads to achievement; nothing can be done without hope.” Hope is the fuel for achievement, resilience, and growth. Without it, we wither.

There are plenty of reasons to worry, and many are beyond our control. Americans fret about the economy, unemployment, crime, violence, climate change, poverty, racism, moral decline, polarization, corruption, education, and inequality. Elsewhere, people add war, terrorism, hunger, and housing to the list. Some problems seem unsolvable. Why do people commit murder? Why are we still plagued by racism, violence, and corruption? Why do poverty and polarization persist? These questions can feel hopelessly unanswerable.

But as management consultant Peter Drucker once said, “The most serious mistakes are not being made as a result of wrong answers. The truly dangerous thing is asking the wrong questions.” Maybe before we surrender to despair, we should ask different questions: “Were we created in the image of a God from whom we have strayed?” “Could this God offer hope and power to save us from ourselves?” If the answer is yes, then hope is not just wishful thinking—it’s a solution within reach.

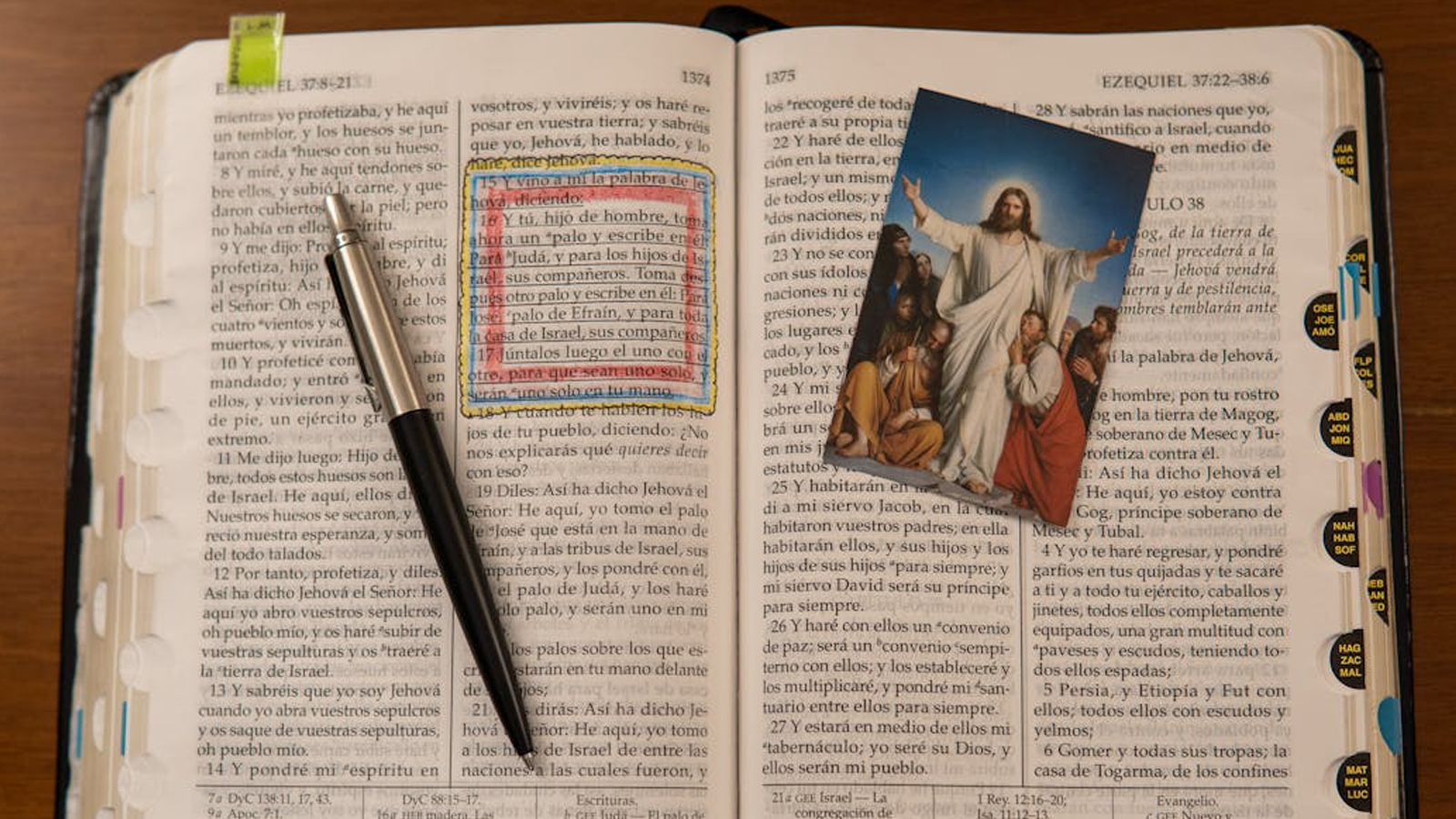

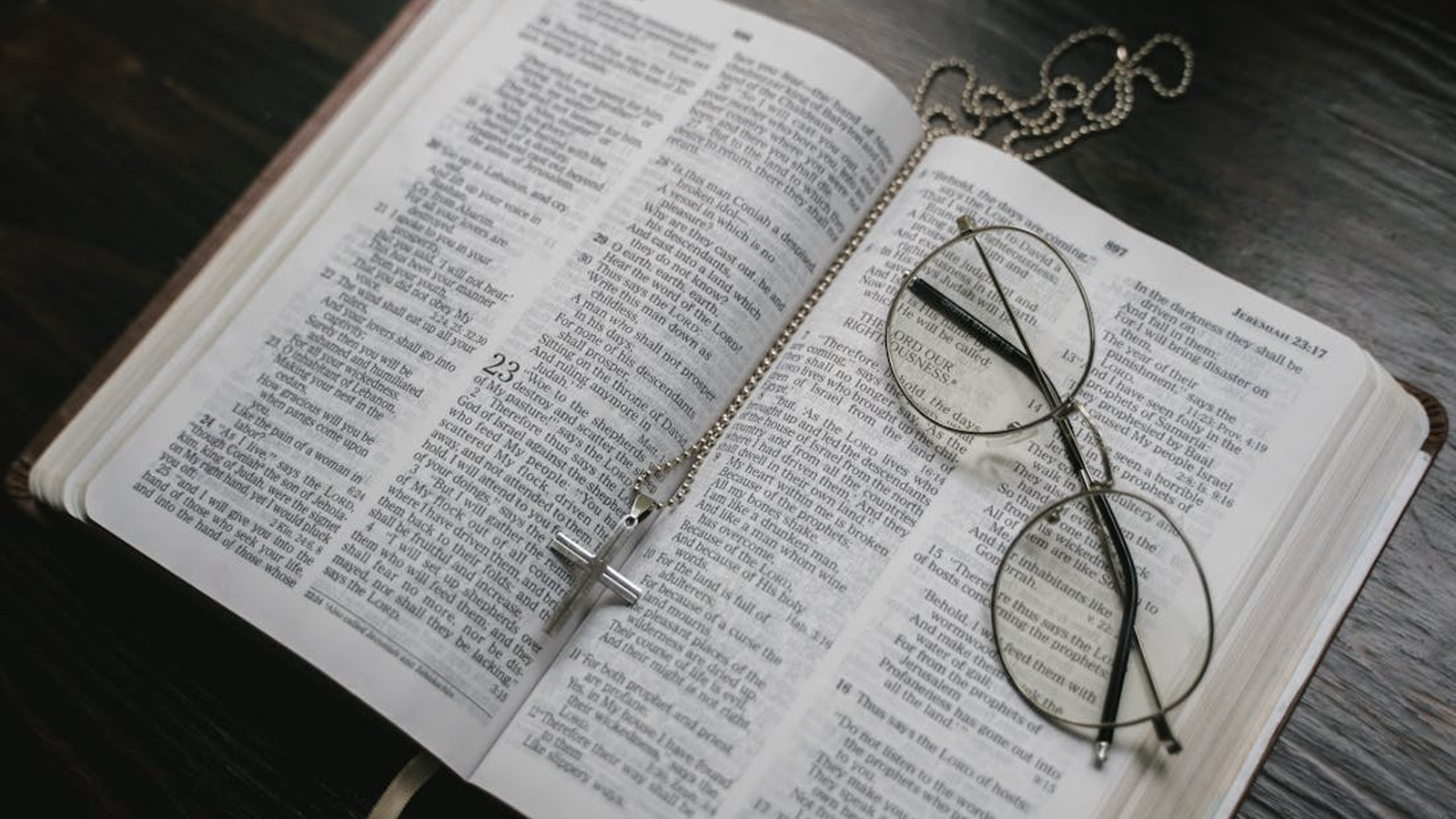

Research backs this up. People who find meaning in life and explore their spirituality are more optimistic. Religious belief is a powerful antidote to hopelessness. It lowers depression, protects against suicidal thoughts, and helps people recover from illness. But not all faith is equally effective. Those who believe in a God who cares personally—a God who listens, saves, and offers eternal life—are the most hopeful, even in the face of trauma or terminal disease. Religious belief is a powerful antidote to hopelessness. It lowers depression, protects against suicidal thoughts, and helps people recover from illness. Share on X

Christians believe in just such a God. Jesus knows us, cares for us, listens to our prayers, and offers salvation and eternal life. In Him, hope is more than a feeling—it’s a promise that can lift us out of despair.

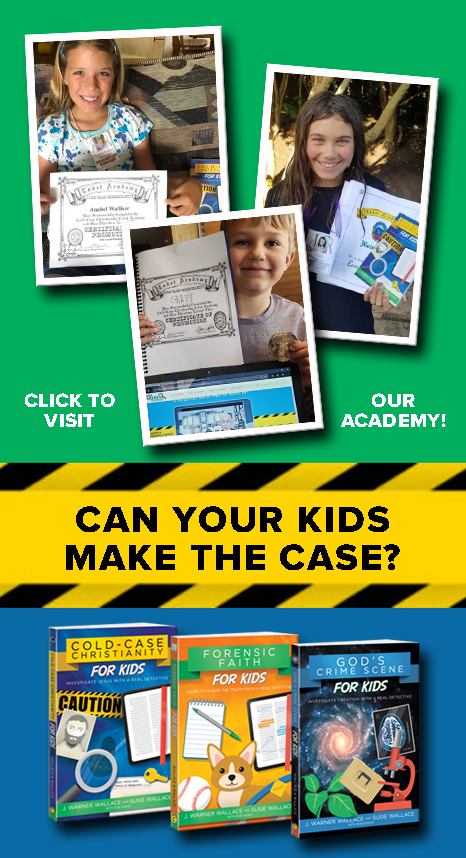

To learn much more about how hope impacts human flourishing and establishes the reliability of the Biblical record, please read The Truth in True Crime: What Investigating Death Teaches Us About the Meaning of Life.