In all the years I’ve spent in criminal trials, I’ve yet to investigate or present a case in which there wasn’t a number of questions the jury simply could not answer. Although my cases are typically robust, cumulative, and compelling, they always have some informational limit. A recent case was an excellent example; jurors convicted the defendant even though they couldn’t answer the following questions: How precisely did the defendant dispose of the victim’s body? How did he find time to clean up the crime scene? What did he do with the murder weapon? How did he move the victim’s car without being seen?

Some questions simply cannot be answered unless a suspect is willing to confess to the crime (and that doesn’t happen often). The existence of unanswered (and unanswerable) questions is such a common part of jury trials that prosecutors typically ask jurors (prior to their selection) if they require every question be answered before they can render a decision. When potential jurors say they need every question answered, we simply remove them from consideration.

Jurors make decisions even though they have less than complete information, and they aren’t the only people who make decisions in this way. Regardless of theistic (or atheistic) worldview, we all trust something is true, even though we can’t answer all the questions. Today, I am a Christian because the evidence for God’s existence and the reliability of the New Testament are robust, cumulative, and compelling. This doesn’t mean all my questions are answered. They aren’t. But I’ve reached a conclusion based on the evidence I do have in much the same way a jury reaches a decision. In a strict sense, this is actually an “act of faith,” given that I trust in something I can’t fully demonstrate or understand. But my “faith decision” is more akin to “trusting in the best inference from the evidence” than “believing blindly” or “believing in something in spite of the evidence.” Jurors make decisions even though they have less than complete information, and they aren’t the only people who make decisions in this way. Share on X

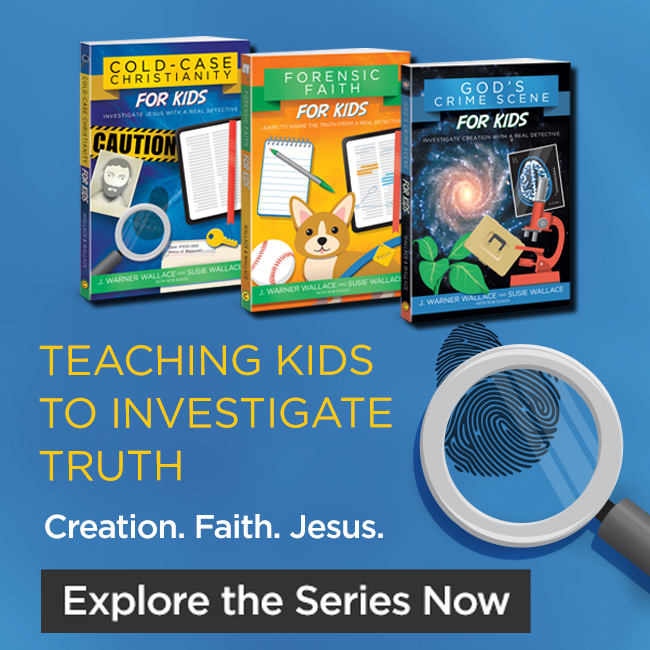

This short article was excerpted from Forensic Faith: A Homicide Detective Makes the Case for a More Reasonable, Evidential Christian Faith. For more information about this third book in my Christian Case Making trilogy, please visit www.ForensicFaithBook.com.

J. Warner Wallace is a Dateline featured Cold-Case Detective, Senior Fellow at the Colson Center for Christian Worldview, Adj. Professor of Christian Apologetics at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, author of Cold-Case Christianity, God’s Crime Scene, and Forensic Faith, and creator of the Case Makers Academy for kids.

Subscribe to J. Warner’s Daily Email

Save

J. Warner Wallace is a Dateline featured cold-case homicide detective, popular national speaker and best-selling author. He continues to consult on cold-case investigations while serving as a Senior Fellow at the Colson Center for Christian Worldview. He is also an Adj. Professor of Christian Apologetics at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, and a faculty member at Summit Ministries. He holds a BA in Design (from CSULB), an MA in Architecture (from UCLA), and an MA in Theological Studies (from Gateway Seminary).