“I have always avoided using the word ‘evil’ when covering terrible events, even those in Bosnia and Kosovo that would later be labeled war crimes. I was of a generation educated to believe that ‘evil’ was a cartoonish moral concept, a word we used only when we didn’t know what madness or imagined infraction might drive human beings to commit murder, even on a mass scale.”

Simon candidly revealed a cultural understanding of “evil” as “a cartoonish moral concept.” Evil, under this definition, is simply a subjective, cultural construct created to explain “what madness or imagined infraction might drive human beings to commit murder.” If this is true, nothing is truly evil; we’re just using this word as a form of subjective, cultural expression.

But that doesn’t seem to capture what really happened in Syria. The painful execution of innocent children is objectively evil. It’s not a matter of personal or cultural opinion, and it’s more than a convenient word. The events in Syria demonstrated the existence of true evil. Perhaps Simon struggled to recognize evil in this way because he interpreted it through a secular worldview. Evil, as it was exhibited in Syria, is best explained by a theistic worldview. In fact, the massacre in Syria demonstrates the existence of God.

I first wrestled with the nature of evil as a homicide detective in Los Angeles County. I had a particularly difficult time investigating cases in which small children were murdered. The horror of these crimes was clear from an emotional perspective, but I began to wonder if that was the only reason we called such crimes “evil”. Is it only because they make us feel a certain way or because we don’t happen to like these kinds of acts? Is it really a matter of subjective, personal or cultural opinion, or are these kinds of murderous acts truly, objectively evil? In other words, are we the only moral standard, or is there an overarching, transcendent standard of “good” by which we judge something to be “bad” or “evil”?

I was an atheist until the age of thirty-five, and shortly after becoming a Christian I began to read the works of C. S. Lewis, the British novelist and Christian apologist. Like me, Lewis was once an atheist who pondered the definition of evil. In his book, Mere Christianity, he described how he even used evil as an argument against God until he realized that true evil required a true, objective standard of good:

“My argument against God was that the universe seemed so cruel and unjust. But how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing this universe with when I called it unjust?”

If evil is simply a matter of personal or cultural opinion, we could eliminate it from the face of the earth but simply changing our minds. But changing your opinion about what happened to the innocent people who were killed in Syria won’t make it any less evil. When Lewis realized the connection between true evil and the necessity of a true standard of good, he began to turn a corner in his thinking:

“Of course I could have given up my idea of justice by saying it was nothing but a private idea of my own. But if I did that, then my argument against God collapsed too – for the argument depended on saying that the world was really unjust, not simply that it did not happen to please my private fancies.”

Evil transcends our opinions and “private fancies.” It’s more than a cultural construction; it’s more than a convenient word. True, transcendent evil requires the existence of a true, transcendent standard of good. Theism provides this kind of standard, because it’s grounded in the existence and nature of an objectively good Law Giver who transcends history and cultural opinion. Unless there exists such a transcendent source and standard, all “evil” is grounded in the subjective opinions of persons or people groups. If that’s true, those who committed the atrocity in Syria could simply argue that, in their cultural opinion, what they didn’t wasn’t evil after all.

But we know better. Scott Simon finished his article by admitting the following:

“I still avoid saying ‘evil’ as a reporter. But as a parent, I’ve grown to feel it may be important to tell children about evil, as we struggle to explain cruel and incomprehensible behavior they may see not just in history — in whatever they will learn about the Holocaust, Bosnia, Rwanda, and Darfur — but in our own times.”

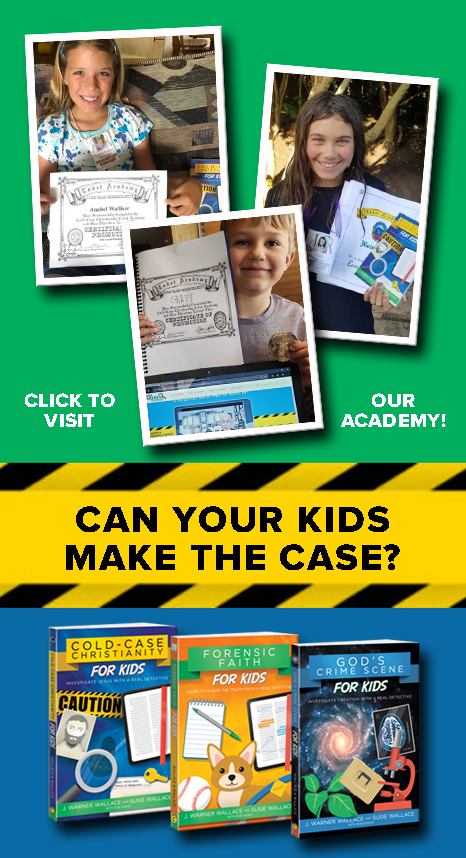

I’m encouraged that Simon has become more thoughtful about his use of the word “evil,” and I hope he eventually begins to think more deeply about what the word requires. Those of us who acknowledge the existence of God need to be equally thoughtful and prepared to show others why true evil requires a theistic worldview. And, of course, it can’t stop there. We also need to be ready to explain why an all-loving, all-powerful God, would allow such evil to exist. Atheists and theists alike have a duty to explain and respond to evil. As believers, we must develop a forensic faith that is knowledgeable, observant and ready to respond. If we can do that, we’ll be able to accurately define what happened in Syria and show how true evil demonstrates the existence of God.

This article was originally posted as an Op-Ed at the Christian Post. Some of the subject matter discussed here is excerpted from Forensic Faith: A Homicide Detective Makes the Case for a More Reasonable, Evidential Christian Faith.

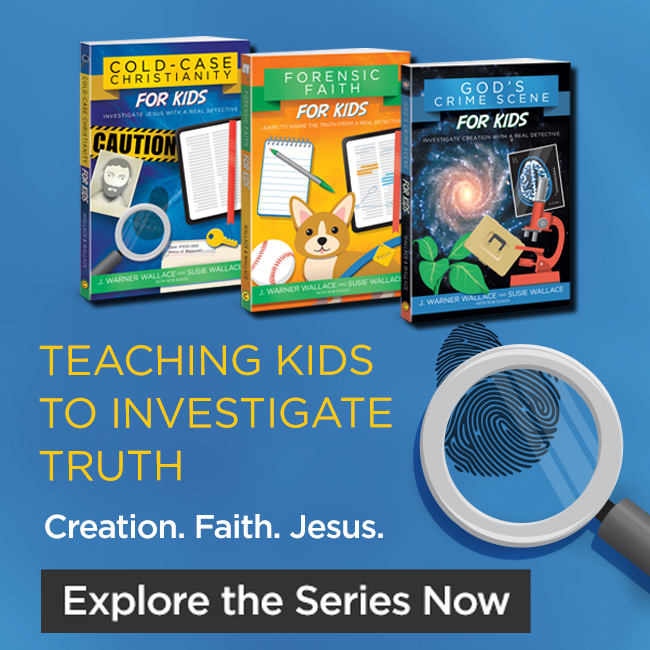

J. Warner Wallace is a Dateline featured Cold-Case Detective, Senior Fellow at the Colson Center for Christian Worldview, Adj. Professor of Christian Apologetics at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, author of Cold-Case Christianity, God’s Crime Scene, and Forensic Faith, and creator of the Case Makers Academy for kids.

Subscribe to J. Warner’s Daily Email

J. Warner Wallace is a Dateline featured cold-case homicide detective, popular national speaker and best-selling author. He continues to consult on cold-case investigations while serving as a Senior Fellow at the Colson Center for Christian Worldview. He is also an Adj. Professor of Christian Apologetics at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, and a faculty member at Summit Ministries. He holds a BA in Design (from CSULB), an MA in Architecture (from UCLA), and an MA in Theological Studies (from Gateway Seminary).