Evil has always been one of the most common challenges raised against belief in God. I’ve faced that question many times — not just in philosophy classrooms or public debates, but at crime scenes and in living rooms where grief hangs heavy. As a homicide detective, I’ve stood with families asking the unanswerable: “Why did this happen to my daughter?” Those are moments that strip away all pretense. They force us to confront the brutal, emotional punch of the “problem of evil.”

When you investigate tragedies up close, you quickly learn that the causes of horrific events are complex. A series of choices and circumstances intersect in ways no one could have fully predicted. As I’ve tried to explain these realities to families, I’ve also had to wrestle with a deeper question: why would a good God allow this level of suffering? It’s a question that doesn’t go away easily, and one that demands more than simple clichés.

Yet there’s something profoundly revealing in the very act of calling something “evil.” The minute we describe an action or event as “evil,” we’re appealing to a moral category beyond mere dislike or preference. It’s not enough to say, “I just don’t like what happened.” There’s a gut-level conviction in us that what happened is wrong — not just for me, but for everyone, everywhere. That sense of moral outrage points beyond subjective opinion; it suggests that evil is an objective reality.

If, however, evil is real — truly, objectively real — then there must be something that defines what “good” is. In order to call something broken, you must first know what “whole” looks like. To call something crooked, you must first have a concept of straight. Similarly, to recognize evil as more than personal preference, there must be a fixed, transcendent standard of goodness by which we measure actions and events. In order to call something broken, you must first know what “whole” looks like. To call something crooked, you must first have a concept of straight. Share on X

Here’s where the argument turns back on itself. Many people use the existence of evil to argue against God — “How could a loving God allow such things?” — but the very concept of “evil” only makes sense if there is a moral standard above humanity. Without God, morality becomes a matter of opinion. Remove the divine lawgiver, and you remove the foundation for moral law. In a purely material universe, things simply happen — there is no “ought,” only “is.” You could erase “evil” entirely just by changing your mind about what counts as wrong, but that’s not how any of us experience the world. Deep down, we know that murder, cruelty, and injustice are truly evil.

So where does that moral intuition come from? Christianity offers a coherent answer: evil exists because good exists — and ultimate good is grounded in the character of God Himself. God isn’t just another being who chooses to act righteously; His very nature defines righteousness. We call acts evil precisely because they depart from His character. Evil, then, is not evidence against God — it’s evidence for Him. It reveals that we live in a moral universe, one that reflects His moral nature.

This doesn’t remove the emotional sting of tragedy, and it doesn’t quiet every cry of “why.” But it reframes the way we approach those cries. When we recognize that the existence of evil actually presupposes an objective good, we begin to see that our moral outrage is an echo of God’s own justice — a sign that His image is stamped in us. The question of why He allows evil is difficult, but the recognition that evil exists points directly back to a righteous Creator.

In the end, every time someone calls something “evil,” they are pointing, often unknowingly, toward the very foundation they claim doesn’t exist. To acknowledge evil as real is to acknowledge goodness — and to acknowledge goodness is to acknowledge God. Far from disproving His existence, evil reminds us we cannot make sense of morality without Him.

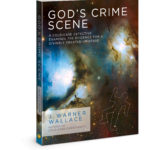

For more information about the scientific and philosophical evidence pointing to a Divine Creator, please read God’s Crime Scene: A Cold-Case Detective Examines the Evidence for a Divinely Created Universe. This book employs a simple crime scene strategy to investigate eight pieces of evidence in the universe to determine the most reasonable explanation. The book is accompanied by an eight-session God’s Crime Scene DVD Set (and Participant’s Guide) to help individuals or small groups examine the evidence and make the case.

For more information about the scientific and philosophical evidence pointing to a Divine Creator, please read God’s Crime Scene: A Cold-Case Detective Examines the Evidence for a Divinely Created Universe. This book employs a simple crime scene strategy to investigate eight pieces of evidence in the universe to determine the most reasonable explanation. The book is accompanied by an eight-session God’s Crime Scene DVD Set (and Participant’s Guide) to help individuals or small groups examine the evidence and make the case.